By Jeremy Sexton

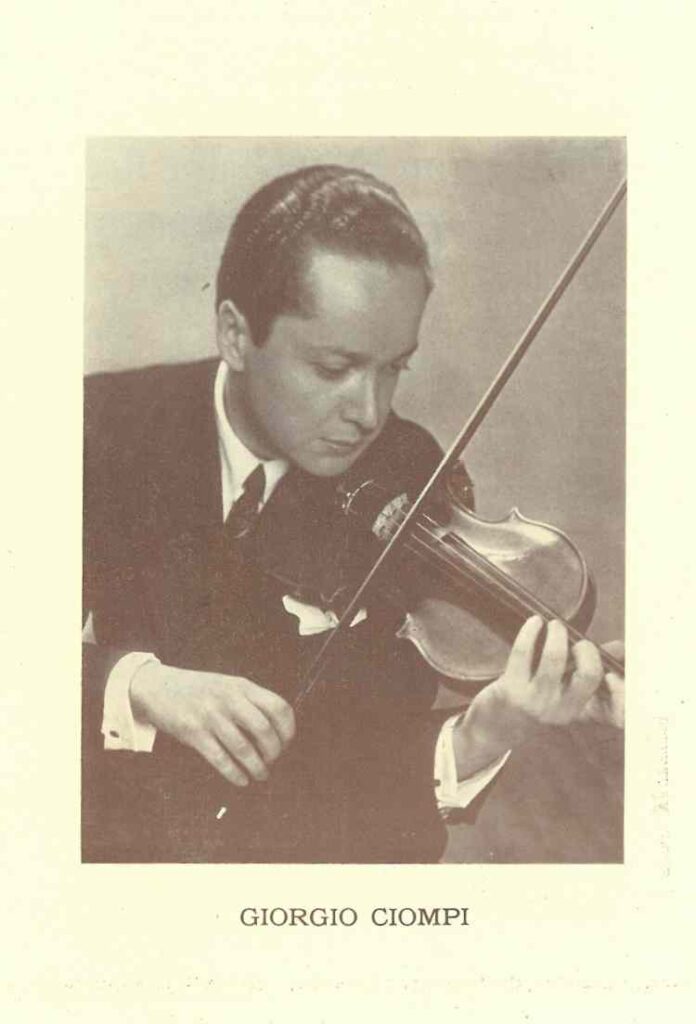

Duke University’s resident string quartet, the Ciompi Quartet, is named after a prodigious Florentine violinist born in 1918: Giorgio Ciompi. After earning a reputation as a child soloist, Ciompi studied violin with Jules Boucherit at the Conservatoire de Paris, won the conservatory’s prestigious premiere prix de violon upon receiving his diploma in 1935, and completed two years of further study with violinist and composer George Enescu. In 1940, by the age of 22, Ciompi had already toured Europe, received glowing press reviews comparing him to such virtuosi of the past as Niccolò Paganini and Eugène Ysaÿe, and obtained an appointment to a teaching position at the Conservatorio Benedetto Marcello in Venice. He seemed poised for superlative success.

The crisis of World War II would soon disrupt Ciompi’s budding career, however. While serving with the Italian Red Cross between 1942 and 1944, the young musician saw his beloved Guarneri violin narrowly escape Nazi machine gun fire. Ciompi tried to contribute to a postwar renewal of the arts in Italy, but the climate of destruction, loss, and economic depression stifled his attempts to reboot his career. He resolved to emigrate to the United States.

Opportunity for the move arose in 1947, when the famed Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini invited Ciompi to join the NBC Symphony Orchestra in New York City. In 1948, while still playing for Toscanini, he joined the Albeneri Trio with cellist Benar Heifetz and pianist Erich Itor Khan. The esteemed trio toured the U. S. and Europe and made several recordings. This first serious engagement with chamber music instilled in Ciompi a love of the genre. He would later compare the intimacy of chamber music to that of marriage: for Ciompi, this was “the best form of music.” He remained a member of the trio even when he left New York in 1954 to become the head of the violin department at the Cleveland Institute of Music.

Ciompi’s move to Durham, North Carolina in 1964 was concurrent with the historical implementation and expansion of artist-in-residence programs in American universities. At Duke University, funding from the Mary Duke Biddle Foundation provided for such an appointment. Ciompi was already familiar to the Duke community, having performed on campus multiple times with the Albeneri Trio. The environment at Duke, in turn, appealed to Ciompi’s lively interest in pedagogy and provided him an unparalleled opportunity for the reflective pursuit of his musical goals. An experienced conservatory teacher already, he must have seemed a natural choice for the position.

Chronology of Quartet Membership

First Violin

Giorgio Ciompi: 1965–83.

Bruce Berg: 1984–94.

Eric Pritchard: 1995–present.

Second Violin

Arlene DiCecco: 1965–73.

Claudia Erdberg: 1973–81.

Claudia Bloom: 1982–1990.

Hsiao-mei Ku: 1990–present.

Viola

Julia Mueller: 1965–75.

Bruce Plumb: 1975–79.

George Taylor: 1979–86.

Jonathan Bagg: 1986–present.

Cello

Luca DiCecco: 1965–73.

Sharon Robinson: 1973–74.

Fred Raimi: 1974–2018.

Caroline Stinson: 2018–present.

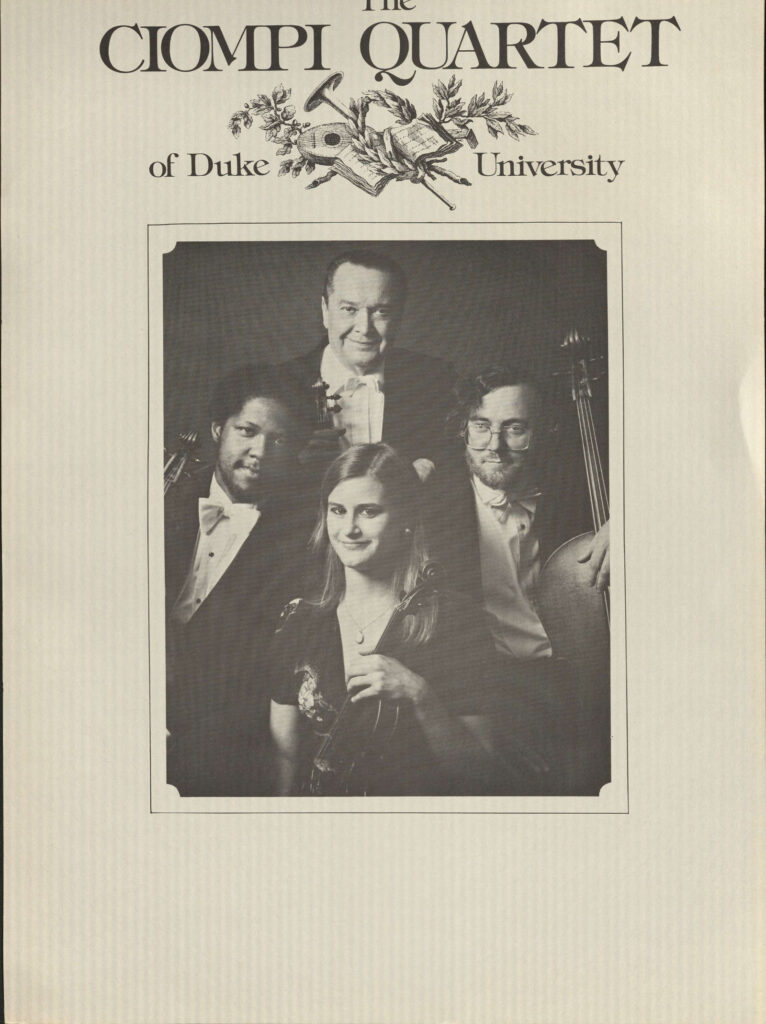

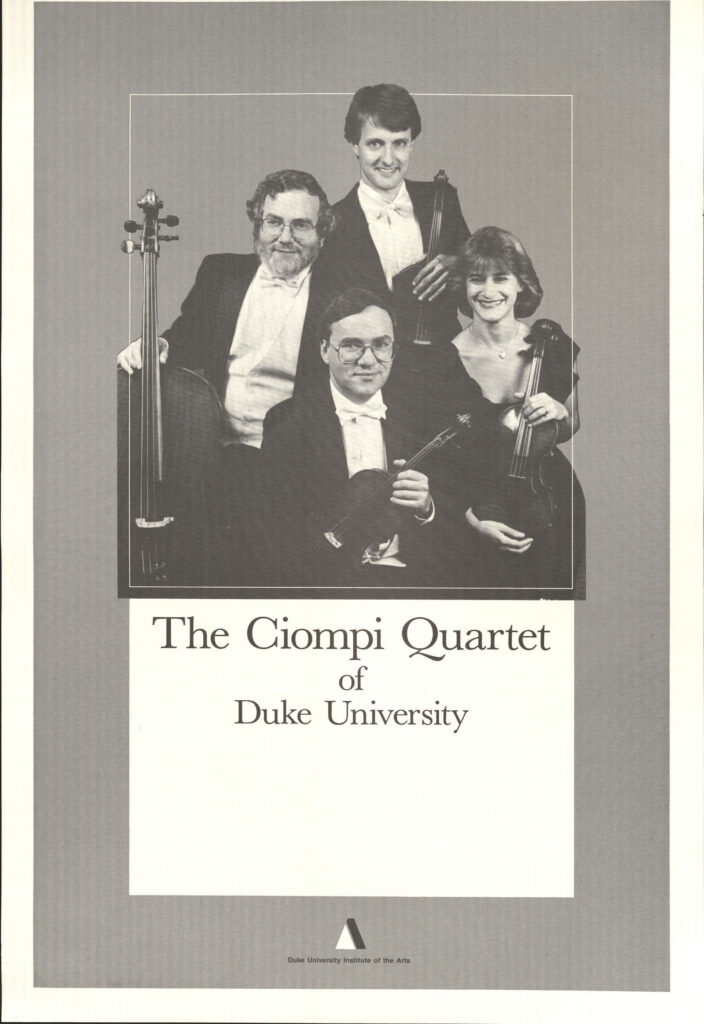

The Ciompi Quartet was a product of the collaborative networking that the presence of an artist in residence at a university makes possible. During one such collaboration, Ciompi’s fellow soloist for a performance of Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins in D Minor with the Duke Symphony Orchestra was Julia Mueller, a Duke professor of violin and viola. Having left the Albeneri Trio to accept the position at Duke, Ciompi now sought a new outlet for his love of chamber music and recruited Mueller as the violist for a new string quartet. The two of them joined forces with a wife-husband team, Arlene Di Cecco and Nicholas Di Cecco of Converse College, who played second violin and cello. Billed as the “Ciompi Quartet,” the group debuted on July 11, 1965 in the Engineering Auditorium on Duke’s West Campus.

Concert programs document at least three more public performances that year, including one on campus sponsored by the Department of Music, one sponsored by the Augusta Music Club in Georgia, and one at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D. C. that was recorded for radio broadcast by the city’s local NPR station, WAMU. These early successes led to the appointment of the Ciompi Quartet as quartet-in-residence at Duke in 1966—essentially an expansion of Ciompi’s individual artist-in-residence position. Both Arlene and Luca Di Cecco began teaching at Duke, and Luca soon was appointed Assistant Professor in the Music Department. Ciompi and Mueller maintained studios as well. In this sense, the Ciompi Quartet has been genuinely resident at Duke throughout its entire history: its members have always taught Duke students, and the ensemble has always balanced its vital pedagogical role in the culture of the university with its performing and touring.

The four original members of the quartet continued performing together until 1973, when the Di Ceccos left to join the Rowe String Quartet and to establish the Garth Newel Music Center in Hot Springs, Virginia. After Mueller’s retirement in 1975, Ciompi himself was the only founding member who remained in the quartet. Nevertheless, an inflow of talented young players enabled the ensemble’s reputation to keep growing under Ciompi’s seasoned leadership. “An exciting blend of youth and experience,” wrote a reviewer for the Macon Times in 1978.

Under Ciompi’s leadership during its first two decades, the Ciompi Quartet surged onto the musical map of the United States. Earning a reputation as the finest quartet in the Southeast, it received rave reviews close to home (e. g. the Durham Sun, the Durham Morning Herald, the Raleigh News & Observer) and farther away (e. g. the New York Times, London, Venezuela). Nationally and internationally, the Ciompi Quartet became known for its technical polish, the “Romantic” or “expressive” sensibility of its interpretations, and an excellent balance between strong ensemble and individual expression. Locally, the ensemble achieved recognition as a cultural gem of North Carolina’s Triangle Area, where it attained a growing public of committed concertgoers. And on campus, Ciompi himself enthusiastically initiated the quartet’s tradition of bringing music directly to Duke undergraduates by playing for them informally in their dorms.

The “Romantic” Ciompi Style

As one thumbs through press clippings related to the Ciompi Quartet during its earliest years, a curious detail emerges. During Ciompi’s own tenure with the quartet (1965-83), the group was known for its “Romantic” mode of musical interpretation. Critics’ reports abound with discussion of “romanticized” and “expressive” interpretations that employ frequent portamenti and rubato. The critical reception of these interpretations varied depending on the critic and the repertoire being reviewed, but commentators concurred in tracing these characteristics to Ciompi himself.

Giorgio Ciompi’s death in November 1983 marked the beginning of a period of change and redefinition for his eponymous quartet. Between 1983 and 1995, the personnel of the quartet went no more than four years at a time without changing. A chamber ensemble’s style and identity are closely tied to the personalities and relationships among its members. As longtime Ciompi Quartet cellist Fred Raimi noted, it can take as long as two years for a group to “gel” after a personnel change. For this reason, some ensembles opt to dissolve to rather than fill a place vacated by a player. And Giorgio Ciompi was not just a player: by all accounts, he was an almost larger-than-life figure whose leadership had defined the quartet and provided a sense of continuity despite the personnel changes that occurred during his lifetime. Absent this leadership, the quartet struggled initially to redefine itself.

Despite these challenges, the quartet maintained a high level of technical competence during this period and continued to be a mainstay in the cultural life of the Triangle. A noteworthy achievement was the performance, between 1988 and 1990, of the full cycle of Beethoven’s string quartets. As well, developments during this period pointed to some ways in which the Ciompi Quartet would continue to grow and evolve in the coming years. In particular, while the ensemble continued to perform the canonical string quartet literature, it also grew more adventuresome in its programming of works by twentieth-century composers. Events like Durham’s Winterfest of Contemporary Arts and Duke’s Encounters: With the Music of Our Time offered opportunity and encouragement for such programming.

A noteworthy example is the quartet’s promotion of the brilliant but then-neglected composer Frank Bridge (1879-1941). The Ciompi Quartet played three of Bridge’s four string quartets in the late ’80s and recorded the Fourth Quartet for their first CD (Sheffield Lab, 1991). At the time, this was the only commercially available recording of the work, and its existence did much to raise awareness of this composer and spur a long overdue reappraisal of his music. As well, the first recording of any ensemble is a landmark in itself as a permanent record of the group’s artistry. The Ciompi Quartet has amassed a sizable discography in the years since.

Equally important was the advocacy for new music that the quartet initiated during this period. The ensemble premiered such works as Kenneth Frazelle’s String Quartet (1990) and Donald Wheelock’s Third and Fourth String Quartets (1988 and 1992). In 1991, Duke composer Stephen Jaffe wrote his First String Quartet for the Ciompi Quartet. After premiering the piece at Duke, the ensemble performed it at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D. C. for the awards ceremony of the Friedham Awards, in which the composition won fourth place. They then added the piece to their permanent repertoire, giving performances of Jaffe’s First Quartet for years after its premiere and recording it on the Albany label (1993). Both of Wheelock’s pieces written for the Ciompi Quartet also remained a part of the ensemble’s active repertoire for some years, and the quartet recorded them in 1994. Such treatment of contemporary compositions as equal in stature to canonical works was a great service, considering that new pieces were far more commonly heard once or twice, then abandoned. This fresh emphasis on providing “credible and honest readings of newer works” (as the Durham-based Independent Weekly put it) marked a notable departure from its repertory selections under Ciompi’s leadership and formed a key part of the quartet’s new identity.

The quartet also began significant expansion of its international touring endeavors during this period. Hsiao-mei Ku, who joined the group as second violinist in 1990, had resided in the United States for some years, but she remained well-known in China, her country of birth. She was able to arrange for the Ciompi Quartet to participate in the December 1991 Beijing Mozart Festival commemorating the bicentennial of the composer’s death. On December 20 of that year, the quartet played at the festival and gave a masterclass at the Central Conservatory in Beijing. On December 21, they performed again in Ku’s hometown of Guangzhou. The visit was a historical landmark: at this time, it was almost unheard of for a Western string quartet to be invited to China, a nation still struggling to recover from the effects of the Cultural Revolution. People there were hungry to experience Western classical music, and Ciompi violist Jonathan Bagg recalled being warmly received and treated “like royalty” during the trip. Though the Ciompi Quartet had toured periodically since its origins in the 1960s, these tours were confined to The Americas, Europe, and Australia—locations within the “the West.” This trip to China marked the beginning of a shift toward a more global conception of the quartet’s possible reach.

The Ciompi Quartet at Home and Abroad

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Ciompi Quartet’s profile is that it has always been both a local and an international ensemble: its consistent standards of excellence have earned the group a national and international reputation, yet it has remained active and involved in the Durham community. Two significant events of the late 1970s and early 1980s illustrate this duality: the quartet’s residency at the Duke University Medical Center and its international tours of 1976.

With the arrival of Eric Pritchard as first violinist in 1995, the ensemble entered a period of some twenty-three years during which its personnel remained constant: first violinist Pritchard, second violinist Ku, violist Jonathan Bagg (since 1986), and cellist Fred Raimi (since 1974). In this particular combination of musicians, the quartet seems to have found a set of personalities that worked particularly well together. Almost immediately, reviewers noted a “quantum leap” in the quality and urgency of the ensemble’s playing. By the time of Raimi’s retirement in 2018, these four musicians had been playing together for longer than Ciompi himself had performed with the quartet.

The ensemble’s commitment to new music grew even stronger during these years. From about 1994 forward, it was the exception rather than the norm for a Ciompi Quartet concert not to include at least one piece less than ten years old. Frequently, such works were composed for the Ciompi Quartet itself: funds from the Duke Institute for the Arts, and later from Duke Performances, enabled many such commissions. A particularly noteworthy collaboration was that between the Ciompi Quartet and the Jewish-American composer Paul Schoenfield. Beginning in 1996, Schoenfield’s Tales from Chelm (1991), a set of four programmatic pieces for string quartet, became one of the Ciompi Quartet’s most frequently performed works. This interest in Schoenfield’s music led to a February 3, 2002 special presentation of the composer’s work by the quartet at Duke’s Freeman Center for Jewish Life, followed by the April 21, 2003 premiere by the Ciompi of a new Schoenfield commission, his String Quartet No. 2 (“Memoirs”). In 2011, the quartet recorded both Tales from Chelm and String Quartet No. 2—the capstone of a 15-year collaboration with this composer.

An Evolving Identity

Like its interpretive manner, the Ciompi Quartet’s programming choices in its early years reflected Giorgio’s own proclivities. The backbone of the ensemble’s repertory at this stage consisted of the canonical string quartet literature: works from the Austro-Germanic tradition by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Dvorak, and Brahms, along with Debussy and Ravel. To this pool were added some twentieth-century works, predominantly music by Walter Piston, Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland, Darius Milhaud, Ernest Bloch, Dmitri Shostakovich, and Béla Bartók. These selections reflect Giorgio’s own aversion to the most dissonant modern music.

Indeed, the Ciompi Quartet’s programming from the late 1990s and early 2000s seems to reflect a strong interest in Jewish culture. In addition to Tales from Chelm, which is based upon Eastern European Jewish folklore, the quartet also performed Osvaldo Golijov’s The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind (1994), a programmatic work about the struggle of maintaining one’s faith in the face of the cruelty and harshness of the world; Prokofiev’s Overture on Hebrew Themes (1922); and Erwin Schulhoff’s Five Pieces for String Quartet (1923). (Schulhoff, a German Jewish composer detained by the Nazis, ultimately died in a concentration camp.)

This interest in Jewish culture was represented not just in the Ciompi Quartet’s repertory selections but also in the ensemble’s travel: in 1998, the group visited Jerusalem to play for audiences of Israelis and international visitors. A rare March snowstorm having forced the cancellation of a masterclass and concert at the Rubin Academy, the quartet arranged an evening performance for the residents of their hotel instead. When the lights went out in the hotel during the finale of Schumann’s Piano Quintet, Eric Pritchard shouted “coda!” and the musicians managed to finish the piece despite the disruption. During the same trip, the quartet performed in the city of Ramallah in the West Bank. The ensemble’s willingness to perform for both Israeli and Palestinian audiences constituted an important statement: a musical peace mission to a region perennially fraught with political tensions and an expression of hope that the shared experience of music might help to alleviate some of these tensions.

This was not the only way in which the quartet’s repertoire selections aligned with their travel itinerary or vice versa: the quartet’s interest in China continued to grow as well. In February 2000, for a collaboration with the New York-based ensemble Music From China, the quartet had learned four string-quartet arrangements of Chinese folk songs by the composer Zhou Long. As they had done with Jewish-influenced works such as those of Schoenfield and Schulhoff, the Ciompi made the Zhou arrangements an integral part of their repertoire, performing them in the same concerts with works from the Western canon. When the quartet made a return trip to China in 2003, it brought these folk songs with it in addition to Western Classical and Romantic repertoire.

Two further visits to China, for a total of four, have afforded the quartet opportunities to work with students in China’s fast-expanding conservatories. The quartet also continued to tour in the West, with a notable two-week visit to Europe in 1996, followed by trips to Germany in May 1999 and to Italy in September 1999 and April 2003. Eric Pritchard and Hsiao-mei Ku both remember especially fondly the quartet’s October 1997 visit to Bolivia to present three concerts and to work with local students at the American Cooperative School in Cochabamba. All these travels in Europe, China, and beyond in the 1990s and 2000s constituted an unprecedented expansion of the quartet’s international presence. (Most recently, the ensemble visited Taiwan in 2019 to present two concerts and give a master class.) Within the United States, the quartet expanded its presence at the summer chamber music festivals that had long been a part of its identity, performing at the Highlands Festival in North Carolina and the Monadnock Festival in New Hampshire.

Summer Festivals

One aspect of the Ciompi Quartet’s significance has been its members’ perennial engagement with the chamber music festivals that dot the cultural landscape of the United States and the world each summer. Like many facets of the quartet’s identity, this affinity for summer festivals can be partly attributed to Ciompi himself, who played in the renowned Pablo Casals Festival in Puerto Rico and taught students at the Aspen (Colorado) Festival, the Siena (Italy) Summer Sessions, and the Kneisel Hall Festival in Blue Hill, Maine.

The ensemble’s close work with Duke composers has continued and increased since 1995. After premiering faculty composer Scott Lindroth’s String Quartet (1997), former graduate student Penka Kouneva’s String Quartet No. 2 (1998), and graduate student Mark Kuss’s American Triptych (1996), the Ciompi Quartet added each of these works to its permanent repertoire, as it had Jaffe’s First Quartet. The quartet featured each of these four pieces (including the Jaffe) in a March 1-2, 1999 program of “Music from Duke University” at the Abraham Goodman House in New York City, in addition to recording the pieces by Lindroth and Kuss (in 1998 and 2000, respectively) for commercial release. Closer to home, members of the quartet regularly performed work by Duke composers in two series: Encounters: With the Music of Our Time and the Graduate Composers’ Concerts. The Ciompi Quartet thus continued to champion the work of Duke’s student and faculty composers on both a local and a national scale.

To a very large extent, the quartet continues this vital support of Duke’s composition program today. As recently as 2019, the quartet premiered Scott Lindroth’s Schley Road (2019) with Duke saxophonist Susan Fancher. And in 2020, as graduate student composers struggled to find performances of their work as the coronavirus pandemic forced the postponement of planned collaborations, the Ciompi Quartet’s Portfolio Project helped to compensate for these challenges by commissioning and recording four new compositions by graduate students.

Our story’s return to Durham from the distant lands of China and Israel, Bolivia and New York City, brings us full circle to where the chronicle of the Ciompi Quartet began: with its establishment as quartet in residence at Duke University. The changes that the quartet embraced in order to thrive and continue evolving after the death of its colossal founding father—its vigorous support for new music and its adoption of a more global cultural outlook—built upon but did not replace Giorgio Ciompi’s vision for a Duke-based string quartet. For all its national and international success, the quartet’s greatest significance may lie in the service it continues to provide to its Duke University community on a regular basis.

The Ciompi Quartet remains an essential part of the Music Department’s functioning by performing and inspiring works by faculty and student composers, performing student compositions in music theory and other undergraduate courses, and serving as pedagogues, mentors, and coaches to students. (Professor Hsiao-mei Ku especially stands out as a wise and caring mentor to undergraduates, says her colleague, cellist Caroline Stinson. Since her arrival in the quartet in 2018, Stinson herself has spearheaded a significant expansion of Duke’s undergraduate chamber ensemble offerings, many of which are coached by Ciompi Quartet members.) Until the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the quartet still carried on Giorgio’s tradition of bringing classical music directly to undergraduate students in their dorms and other campus spaces—a tradition, we have reason to believe, that the ensemble will continue to carry long into the future.

Over the course of its lifetime, the Ciompi Quartet has accumulated an impressive array of tours, recordings, and commissions. Its most impressive accomplishment, however, is that it has managed to achieve all of these things while remaining fully present in a community where it acts day-to-day in the service of students and faculty and delights a loyal following of local music-lovers. In this sense, the Ciompi Quartet is certainly one of the great success stories of artist-in-residence programs in the United States.

Giorgio Ciompi at Duke University

Giorgio Ciompi is described by those who knew him as a warm, generous, and outgoing man who, despite his tremendous talent, never seemed aloof from those around him. He filled his office in the Biddle Music Building with photographs of the musical friends to whom he was devoted. He was no less committed to his students: in a 1979 North Carolina Leader article, David Witherspoon recalls being in the midst of an interview with Ciompi when a student called in sick to cancel a violin lesson. Ciompi not only expressed concern for the student’s health but offered personally to bring him chicken soup. The endurance of his legacy at Duke was encapsulated by the dedication of a “Ciompi Room” on Duke’s West Campus in 1991, and by the marking of that space with an annual commemorative concert for several years thereafter.